-

Are the Murdochs too powerful?

- TheSunKing_RupertMurdoch'sEndlessReign (inltv.co.uk)

- TheSunKing_RupertMurdoch'sEndlessReignP2 (inltv.co.uk)

- "Given that Fox is a “central node” of the far-right conspiracy machine, it’s fair to regard the Murdochs as America’s first family of disinformation....." ....

- Please read full article further down this www.inltv.co.uk webpage

- TheSunKing_RupertMurdoch'sEndlessReignP2 (inltv.co.uk)

Rupert Murdoch set to marry for fifth time at 92

-

Published

-

Are the Murdochs too powerful?

-

Published

- Are the Murdochs too powerful? - BBC News

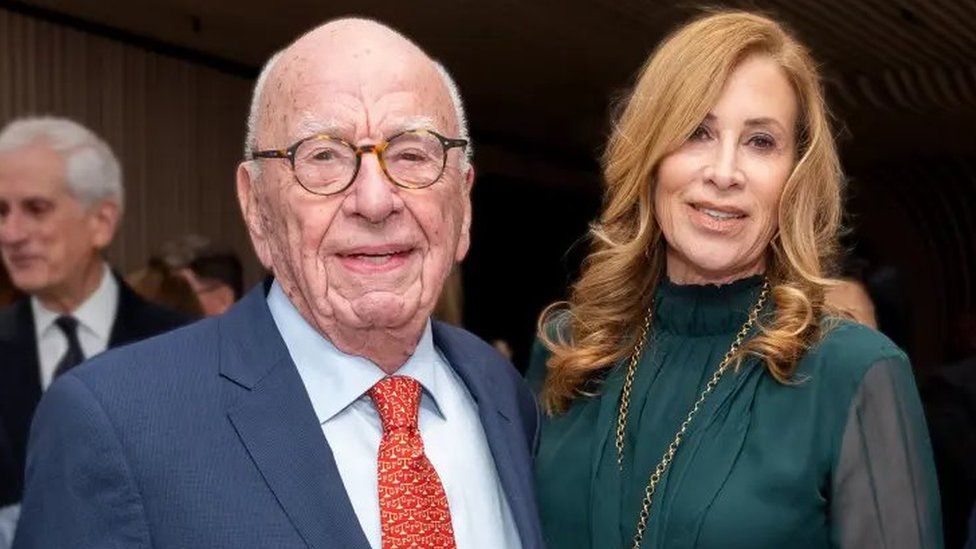

- Mr Rupert Murdoch and Ms Ann Lesley Smith

- Media tycoon Rupert Murdoch has announced his engagement to his partner Ann Lesley Smith, a former police chaplain.

-

The Sun King Rupert Murdoch's Endless Reign Part 2

-

MURDOCH AND ME

Rupert Murdoch may be the world’s most powerful private citizen. After running Murdoch’s Sunday Times of London for 11 years, a noted journalist reveals the triumphs and terrors of working for a 20th-century Sun King.John Dux agrees: “Rupert is the world’s worst manager. During his visits he should have inspired and encouraged his lieutenants. Instead he left them miserable and demoralized with his autocratic style and raging temper. It used to take weeks to restore morale after he had gone.”When you work for Rupert Murdoch you do not work for a company chairman or chief executive: you work for a Sun King. You are not a director or a manager or an editor: you are a courtier at the court of the Sun King—rewarded with money and status by a grateful king as long as you serve his purpose, dismissed outright or demoted to a remote corner of the empire when you have ceased to please him or outlived your usefulness.All life revolves around the Sun King; all authority comes from him. He is the only one to whom allegiance must be owed, and he expects his word to be final. There are no other references but him. He is the only benchmark, and anybody of importance reports directly to him. Normal management structures—all the traditional lines of authority, communication, and decision-making in the modern business corporation—do not matter. The Sun King is all that matters.BY ANDREW NEIL

Please red this full Murdoch and Me story further down this wwwinltv.co.uk webpage

Mar 20, 2023 · Media tycoon Rupert Murdoch has announced his engagement to his partner Ann Lesley Smith, a former police chaplain. Mr Murdoch, 92, and Ms Smith, 66, met in September at an event at his..

Rupert Murdoch Partner is Lord Jacob Rothschild

Business and Financial Leaders Lord Jacob Rothschild and Rupert Murdoch Invest in Genie Oil & Gas Genie Energy Corporation (Genie Energy), a division of IDT Corporation (NYSE: IDT, IDT.C)

FOX NEWS HAS DONE MORE TO INCITE DOMESTIC POLITICAL VIOLENCE THAN DONALD TRUMP

The origins of Fox News’s insidious role can be traced to a 1970 memo from the Nixon White House and Roger Ailes.

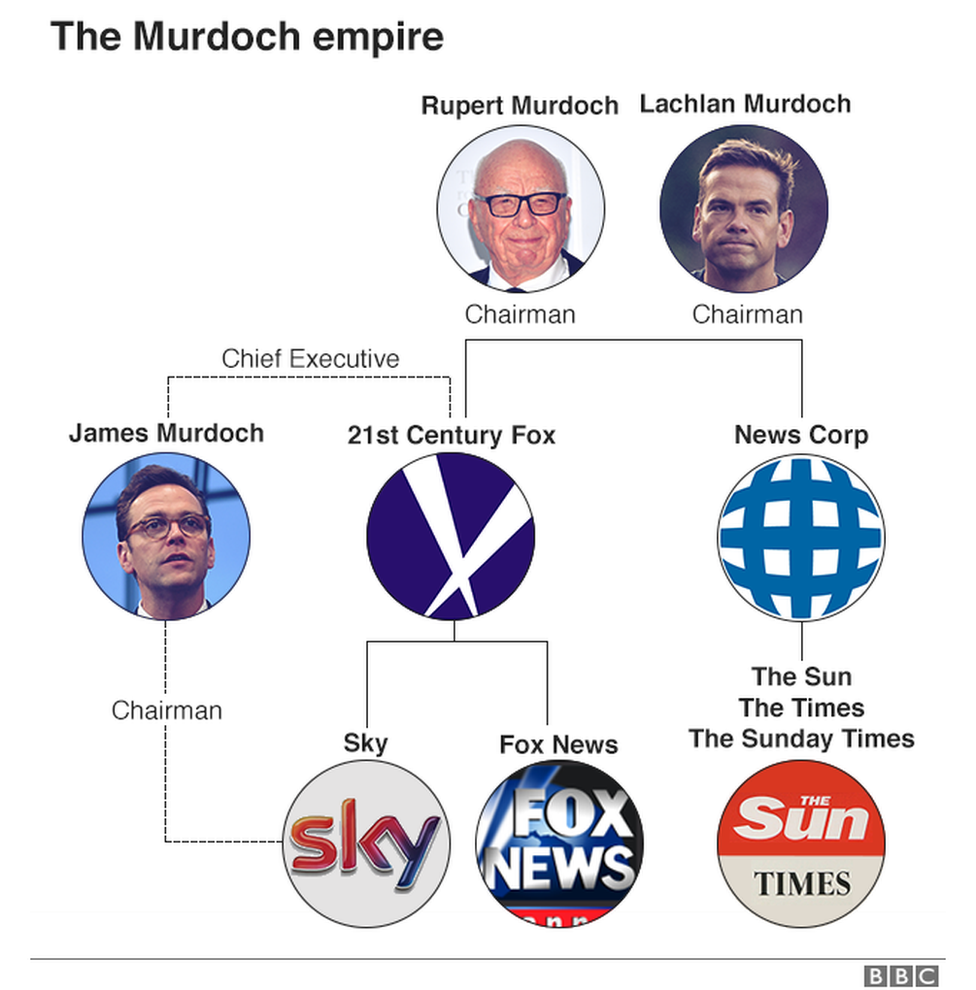

Lachlan Murdoch to claim family empire Published

Lachlan Murdoch to claim family empire - BBC News

Rupert Murdoch had said he was "not worried at all" about Ofcom

Lachlan Murdoch (R) and Rupert Murdoch (L) would be co-chairmen of the new company

Rupert Murdoch Has ‘More Impact Than Any Living Australian’ Says Tony Abbott

Rupert Murdoch's And News Corporation controlled News International phone hacking scandal

"To Beat or subdue or weaken the Enemy, You Have To Understand How The Enemy .:.. and how How The Enemy Operates and Thinks..." .... USA Major Smedley Butler

News Corp a “cancer” on democracy and suggested it should be the subject of a royal commission. “They go after people who have the audacity to raise a question about their behaviour,” Rudd said. He added, “It’s one of the reasons I’m speaking out directly, so that people can have a normal national conversation rather than a continued national embarrassed silence about this.”

Murdoch has a seat on the Strategic Advisory Board of Genie Oil and Gas, having jointly invested with Lord Rothschild in a 5.5% stake in the company which conducted shale gas and oil exploration in Colorado, Mongolia, Israel

Rupert and James Murdoch News Corp Media Empire

First Mafia Bosses Who Didn't Know They Were Running A Criminal Enterprise -

UK News Corp Phone and Email Hacking UK Parliamentary Inquiry

James Murdoch, left, and Rupert Murdoch provide evidence to the Culture, Media, and Sport Select Committee in the House of Commons in London on the News of the World phone-hacking scandal on July 19, 2011.

“Mr. Murdoch, you must be the first Mafia boss in history who didn’t know he was running a criminal enterprise.”.... Mr Tom Watson UK Labour MP and co-author with Guardia journalist Martin Hickman, of the book "Dial M For Murder"

'This book uncovers the inner workings of one of the most powerful companies in the world: how it came to exert a poisonous, secretive influence on public life in Britain, how it used its huge power to bully, intimidate and cover up, and how its exposure has changed the way we look at our politicians, our police service and our press.'

Rupert Murdoch's newspapers had been hacking phones, blagging information and casually destroying people's lives for years, but it was only after a trivial report about Prince William's knee in 2005 that detectives stumbled on a criminal conspiracy. A five-year cover-up then concealed and muddied the truth. Dial M for Murdoch gives the first connected account of the extraordinary lengths to which the Murdochs' News Corporation went to "put the problem in a box" (in James Murdoch's words), how its efforts to maintain and extend its power were aided by its political and police friends, and how it was finally exposed.

The book is full of details which have never been disclosed before in public, including the smears and threats against politicians, journalists and lawyers. It reveals the existence of brave insiders who pointed those pursuing the investigation towards pieces of secret information that cracked open the case.

By contrast, many of the main players in the book are unsavoury, but by the end of it you have a clear idea of what they did. Seeing the story whole, as it is presented here for the first time, allows the character of the organisation which it portrays to emerge unmistakeably. You will hardly believe it.

About the Authors of Dial M for Murdoch: News Corporation and The Corruption of Britain

Martin Hickman has worked for the Independent since 2001, and has driven the paper’s coverage of the phone hacking scandal. He was named Journalist of the Year by the Foreign Press Association in 2009.

Tom Watson is the MP for West Bromwich East. He campaigns against unlawful media practices and led the questioning of Rupert and James Murdoch when they appeared before Parliament in July 2011. He is the deputy chair of the Labour Party.

A Conservative member of the committee, Philip Davies, could not withhold his withering skepticism.

“I find it incredible, absolutely incredible, that you didn’t say, ‘A quarter of a million? Let me look at that,” Davies began. “I can’t begin to believe that that is the action that any self-respecting chief operating officer would take, when so much of the company’s money and reputation is at stake.”

Another member of the committee, Labour’s Tom Watson, went many steps further.

“You’re familiar with the word Mafia?” he asked James.

“Yes, Mr. Watson,” James replied.

“Have you ever heard the term omertà, the Mafia term they use for the code of silence?”

“I’m not an aficionado of such things.”

“Would you agree it means a group of people who are bound together by secrecy, who together pursue that group’s business objectives with no regard for the law, using intimidation, corruption, and general criminality?” Watson asked.

“Again, I’m not familiar with the term particularly,” James replied.

“Would you agree with me that this is an accurate description of News International in the U.K.?”

“Absolutely not,” James responded. “I frankly think that’s offensive and not true.”

Watson was not done.

“Mr. Murdoch, you must be the first Mafia boss in history who didn’t know he was running a criminal enterprise.”

During those hearings, Rupert Murdoch, seated next to James, even had a pie thrown at him by a protester. (Rupert’s wife at the time, Wendi Deng, famously lunged at the pie-thrower.) In the committee’s final report, Rupert was described as “not a fit person” to run a major corporation, and James was criticized for “willful ignorance” and a “lack of curiosity” in finding out what had happened. Deflecting attention from calls for his father to resign, James fell on his sword, shedding his post in London and relocating to New York, where he assumed different duties in his father’s empire. With the aura of disgrace, James was sidelined in the competition to succeed his father.

Elisabeth Murdoch stands with her father, Rupert, as they watch the Cheltenham Horse Racing Festival on March 18, 2010, in Cheltenham, England.

Rupert Murdoch Described As The Most Dangerous Man In The World

Rupert Murdoch In 90 Seconds

Rupert Murdoch Has Trouble Answering Questions At UK Parliamentary Phone Hacking Inquiry

Rupert Murdoch's Toxic Legacy

Rupert Murdoch's Media Empire

Rupert Murdoch Succession Politics

Rupert Murdoch

15Things You Didn't Know About Rupert Murdoch

Rupert Murdoch Setting Political Agenda Through His Media Empire

Rupert Murdoch Early History About His Media Empire ABC Part 1

Rupert Murdoch News Corp History ABC Part 1

Rupert Murdoch 1967 Media Monopolies ABC Part 3

Rupert Murdoch Jerry Hall Marriage Part 1

Rupert Murdoch set to marry for fifth time at 92

-

Published

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/65012754

Rupert Murdoch set to marry for fifth time at 92

-

Published

- Mr Rupert Murdoch and Ms Ann Lesley Smith

- Media tycoon Rupert Murdoch has announced his engagement to his partner Ann Lesley Smith, a former police chaplain.

-

By Emma Saunders - Entertainment reporter

Mar 20, 2023 · Media tycoon Rupert Murdoch has announced his engagement to his partner Ann Lesley Smith, a former police chaplain. Mr Murdoch, 92, and Ms Smith, 66, met in September at an event at his..

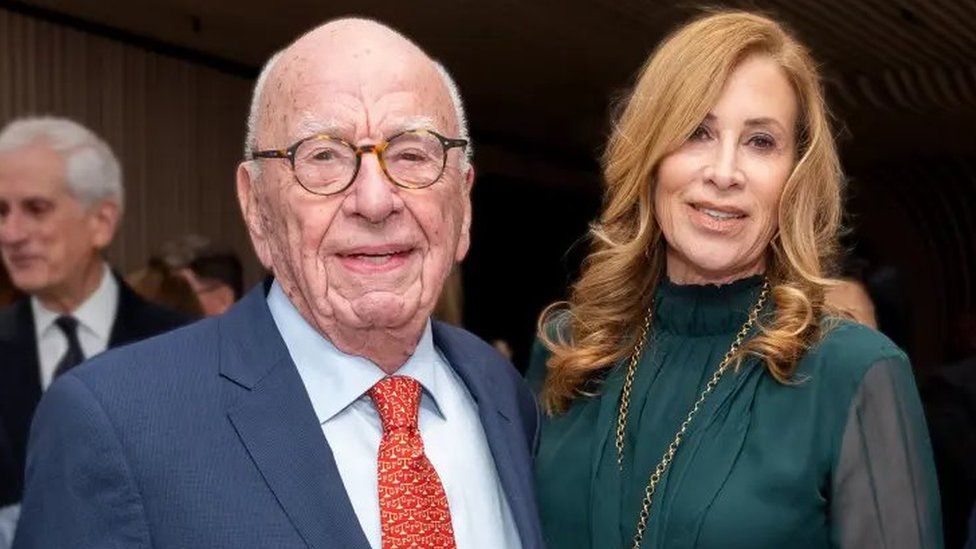

Mr Rupert Murdoch attended the Super Bowl recently with daughter Elisabeth Murdoch (left) and Ann Lesley Smith (right)

Media tycoon Rupert Murdoch has announced his engagement to his partner Ann Lesley Smith, a former police chaplain.

Mr Murdoch, 92, and Ms Smith, 66, met in September at an event at his vineyard in California.

The businessman told the New York Post, one of his own publications: "I dreaded falling in love - but I knew this would be my last. It better be. I'm happy."

He split with fourth wife Jerry Hall last year.

Mr Murdoch added that he proposed to Ms Smith on St Patrick's Day, noting that he was "one fourth Irish" and had been "very nervous".

Ms Smith's late husband was Chester Smith, a country singer and radio and TV executive.

"For us both it's a gift from God. We met last September," she told the New York Post.

"I'm a widow of 14 years. Like Rupert, my husband was a businessman... so I speak Rupert's language. We share the same beliefs."

Mr Murdoch, who has six children from his first three marriages, added: "We're both looking forward to spending the second half of our lives together."

The wedding will take place in late summer and the couple will spend their time between California, Montana, New York and the UK.

Mr Murdoch was previously married to Australian flight attendant Patricia Booker, Scottish-born journalist Anna Mann, and Chinese-born entrepreneur Wendi Deng.

Rupert Murdoch Jerry Hall Marriage - Jerry Hall's Best Dresses

Rupert Murdoch Jerry Hall Divorce Part 2

Rupert Murdoch Jerry Hall Divorce Part 3

Jerry Hall files for divorce from Rupert Murdoch Published

Jerry Hall files for divorce from Rupert Murdoch - BBC News

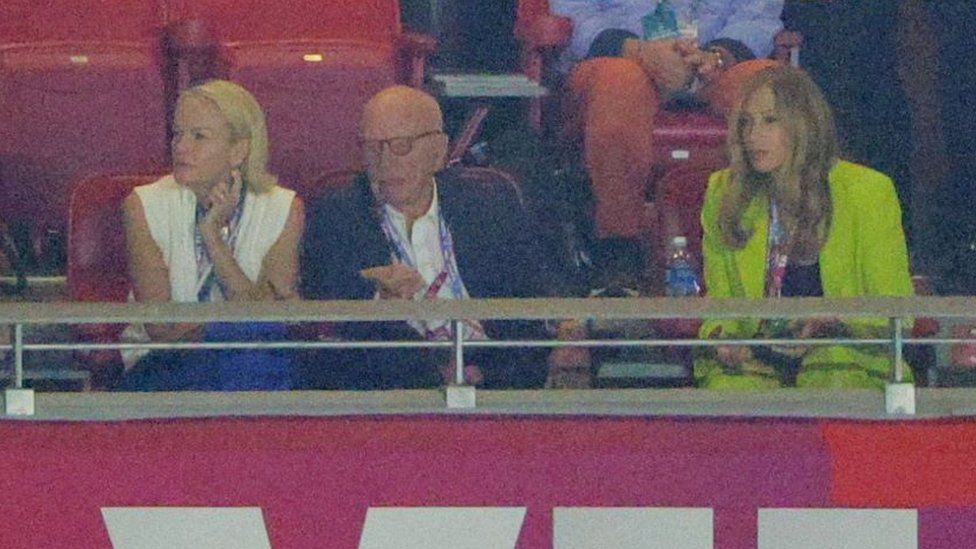

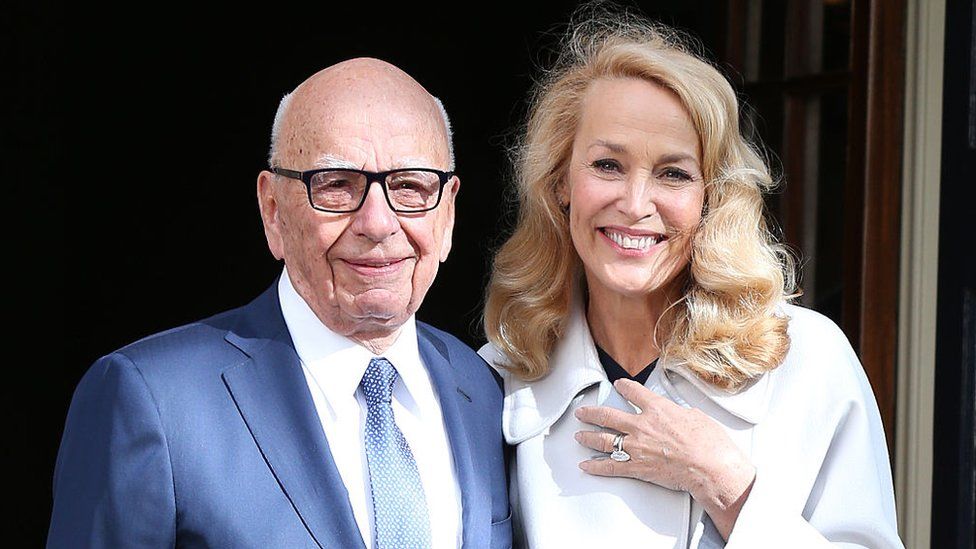

Rupert Murdoch and Jerry Hall at their London wedding in 2016

Jerry Hall has filed for divorce from media tycoon Rupert Murdoch in a court in the US state of California.

The petition cited "irreconcilable differences" between the pair, six years after they married.

The model and actress, 66, is claiming spousal support from the 91-year-old billionnaire, but is still seeking information about the full extent of his assets, the petition said.

Ms Hall was previously the partner of the Rolling Stones' Mick Jagger.

It will be the fourth divorce for Mr Murdoch. US media had said the split had come as a surprise to those close to the family.

Mr Murdoch - whose News Corporation empire controls major outlets including Fox News and the Wall Street Journal in the US, and The Sun and The Times in the UK - was previously said to have been devoting more time to his new wife.

At the time of his marriage, the billionaire announced on Twitter that he was "the luckiest AND happiest man in world", and that he would stop posting on the platform.

In 2018, his elder son Lachlan was named as his successor as chief executive of Fox Corp. Mr Murdoch also sold most of 21st Century Fox to the Walt Disney Company.

The couple had also been spotted together in public on several occasions.

Last year, Ms Hall was seen "doting on" her partner at his 90th birthday party, according to the New York Times.

The Texan model-turned-actress was previously in a long-term relationship with Mr Jagger, with whom she had four children. The pair tied the knot in a Hindu wedding ceremony in Bali, Indonesia, in 1990. The marriage was annulled less than a decade later in London's High Court of Justice, which ruled that the marriage had never been legal under British or Indonesian law.

Mr Murdoch was previously married to Australian flight attendant Patricia Booker, from 1956 to 1967; Scottish-born journalist Anna Mann, from 1967 to 1999; and Chinese-born entrepreneur Wendi Deng, from 1999 to 2014.

Across their marriages, the pair have 10 children.

Rupert Murdoch Considers Combing Fox News And News Corp

Murdoch’s succession: who wins from move to reunite Fox and News Corp?

Deal would seal legacy with favoured heirs, but markets question whether companies should merge in the first place

Rupert Murdoch and eldest son Lachlan pictured in 2015.

Rebekah Brooks and Rupert Murdoch.

Rupert Murdoch with his sons Lachlan (left) and James

This week’s 200th anniversary soiree for the Sunday Times gathered some of the biggest names in media at the headquarters of the British Academy of Film and Television Arts in London’s Piccadilly to celebrate one of the jewels of Rupert Murdoch’s empire.

But talk of famous front pages and scoops among guests at Monday night’s event, where the attendees included News Corp boss Robert Thomson and News UK chief Rebekah Brooks, was overshadowed by the news that broke three days earlier: the mogul’s plan to reunify his media empire.

After a lifetime of deals, Murdoch, now 91, is making perhaps his final play as he seeks to merge News Corp – home to the Times, Sun, Wall Street Journal and the Australian – with Fox, broadcaster of Fox News and crown jewel NFL games, as he hands the running of his empire over to eldest son, Lachlan.

While the 51-year-old heir, who shocked his father by abruptly leaving the family business in 2005 to move to Australia and pursue his own interests before being enticed back a decade later, is primed to become chair, there is plenty of chatter over who will get the top job running the day-to-day business.

Thomson had long been mooted as the one to manage the combined group after a merger – he is Rupert’s right-hand man and the fellow Australian considers him practically a son. But with Lachlan in the driving seat, that is not to be.

Then there is Brooks, another Rupert favourite who has long held ambitions to rise further. However, she lacks international experience, and has the issue of the phone-hacking scandal on her CV, with new allegations brought recently relating to her tenure as Sun editor. (News UK has always denied any hacking took place at that newspaper, saying it only happened at its sister title, News of the World.)

“Lachlan is not going to be running the business day to day. The really interesting question is, who will be?” said a source. “I think it will be Lachlan’s decision who does, not Rupert, and that makes it interesting. Robert has historically been protected, but Rebekah is also powerful – she is the only person all the children talk to. She’s like another sibling and is very close to Lachlan.”

Lachlan, who insiders say was against the decision to downsize the empire by selling 21st Century Fox’s global entertainment assets to Disney for $71bn (£63bn) five years ago, is seeking to rebuild scale in an era of global tech and media giants.

“Lachlan was furious,” says one former senior executive. “I think it was the nail in the coffin when [his brother] James supported it too. James and Lachlan, no matter what anyone says, did get along. After that they stopped speaking. I believe that is still the case now. A scaled-down News Corp is the opposite of what he wants.”

The sale of 21st Century Fox also carved the younger James, once seen as heir apparent, out of the line of succession and ended any possibility of a future potential dynastic struggle.

The 49-year-old resigned from the board of News Corp two years ago, citing “disagreements” over editorial content, understood to include coverage casting doubt on climate change, severing his last formal link to the empire created by his father.

A reunified News Corp and Fox, valued at $9.7bn and $16bn respectively, would create a more muscular $26bn business. This would put it on a par with the market capitalisation of the freshly minted Warner Bros Discovery ($30bn), albeit still a relative minnow compared with beasts such as Disney ($180bn) and Comcast ($134bn), which bought Murdoch’s Sky for £30bn four years ago.

Special boards at each company are now evaluating the merits of a merger, and the relative value of each company to the other in the proposed all-stock deal, but banks and shareholders seem to have made up their mind already.

Investors in Fox and News Corp both believe they are undervalued – shares in each are down 30% over the last year – something analysts suggest a tie-up probably will not solve.

There is also the cautionary tale of the similar recombination of CBS and Viacom after 13 years of separation. The business, now called Paramount, is valued at $12.5bn – less than half the value of the separate businesses before the deal.

“On a standalone basis, this transaction raises more questions than answers as we struggle to see the strategic rationale for combining these two companies,” said Jessica Reif Ehrlich, an analyst at Bank of America, summing up the wider market reaction.

Some investors in the News Corp camp are concerned about the “toxicity” of the rightwing Fox News, and the practical matter of the two multibillion-dollar lawsuits it faces over allegations that it promoted the spread of theories that the US election in 2020 was rigged.

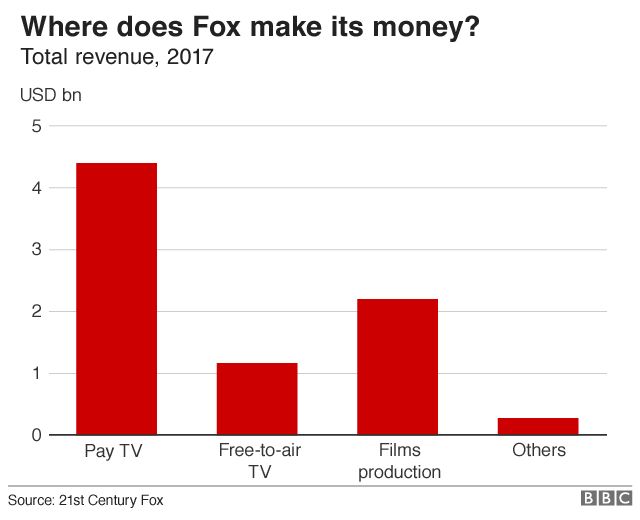

Meanwhile, some Fox investors balk at tying the hugely profitable business to a primarily publishing operation, regardless of the leaps and bounds it has made striking commercially lucrative ad deals with Silicon Valley giants such as Google.

Analysts at MoffettNathanson put Fox on track for record profits of $3.3bn next year, while News Corp made $1.6bn in profits in the year to the end of June, a 31% increase.

To get a deal through will require a majority of non-Murdoch family shareholders.

“There will be some investors in the margin that will have a problem with Fox News in their portfolio,” said a second source. “And the Wall Street Journal [staff] loathes Fox News, they see it as toxic, silly, and think it would harm their brand. But in the end it won’t be overly consequential because Fox News is so damn profitable.”

However, with the Murdochs’ family trust controlling 39% of the voting shares in News Corp and 42% in Fox Corporation, there are good odds they will get their way if the plan gets as far as being put to a shareholder vote.

“I think this has been in the works for two years,” said the former senior executive. “I give it a 75% chance it will happen, 25% that it will be blocked. It’s all about Lachlan. Rupert is in his 90s – this is his last deal, it’s succession planning.”

When the Rupert era ends, the power behind the family trust will be equally split between his four eldest children – Lachlan, James, Elisabeth and Prudence – while his two youngest daughters, Grace and Chloe, are financial beneficiaries.

Whether such a setup could see a situation emerge akin to HBO’s hit drama Succession, which features members of a powerful family vying for control of a sprawling media conglomerate that has drawn endless comparisons with the real-life Murdochs, remains to be seen.

But for now, for Rupert, merging the two businesses he was forced to split against his will almost a decade ago after the phone-hacking scandal is about securing a family legacy after seven decades of deal-making.

“At a certain level of money, it is control that matters the most,” says Claire Enders, founder of Enders Analysis and a longtime Murdoch watcher. “What this transition is about is future control and restoration of the original structure of News Corp and a long-term umbrella for the newspaper assets.”

Despite the negative sentiment from investors and Wall Street about the rationale behind the merger, sources close to Murdoch say the deal is all about business, not family.

“The proposal is 100% based on business rationale which is a combination of complementary portfolios of premium content to create a global leader in news, live sports and information,” said the source. “Any commentary that implies it has to do with succession planning is absurd and comes from sources with no knowledge of the strategy and intent.”

Most viewed

-

Supreme court justices felt tricked by Trump at Kavanaugh swearing-in – book

Supreme court justices felt tricked by Trump at Kavanaugh swearing-in – book -

Sanna Marin suffers defeat in Finland election as SDP beaten into third place

Sanna Marin suffers defeat in Finland election as SDP beaten into third place -

Donald Trump vows to escalate attacks against Alvin Bragg – sources

Donald Trump vows to escalate attacks against Alvin Bragg – sources -

Russian pro-war military blogger killed in blast at St Petersburg cafe

Russian pro-war military blogger killed in blast at St Petersburg cafe -

Thousands queue at Dover for second day as Braverman accused of denial

Thousands queue at Dover for second day as Braverman accused of denial

-

Are the Murdochs too powerful?

- Rupert Murdoch questioned Fox News coverage of stolen US election claims, court documents show Posted Wed 8 Mar 2023

-

Fox's bid to dismiss lawsuit fails

A judge rules Dominion Voting Systems' lawsuit against Fox News Network can go to trial, with the voting machine company alleging Fox defamed it by amplifying conspiracy theories about its technology.

Rupert Murdoch wrote that two of his TV hosts "maybe went too far" on voter fraud claims. - Fox News And The Big Lie Part 1

His comments came to light when an email of his contained in a trove of new exhibits in Dominion Voting Systems' lawsuit against his TV network was unsealed on Tuesday. Dominion Voting Systems sued Fox News Networks for $US1.6 billion ($2.4 billion) in 2021, accusing the cable TV network of amplifying debunked claims that Dominion voting machines were used to rig the election against Republican Donald Trump and in favour of his rival Joe Biden, who won the election.

The reams of documents that became public on Tuesday offer a window into Fox's internal deliberations as it covered the 2020 presidential election, alienating some viewers by being the first network to project that Mr Biden would win the crucial state of Arizona.

The documents show top executives down to show-level producers and hosts discussing concerns about the network's reputation and casting doubt on the plausibility of Mr Trump's claims of election fraud.

More than 6,500 pages were released on Tuesday. However, the full extent of the evidence is not clear as many filings are heavily redacted. Fox has defended its coverage, arguing claims by Mr Trump and his lawyers were inherently newsworthy and protected by the first amendment of the US constitution.

The network said in a statement the documents showed Dominion using "distortions and misinformation" to "smear Fox News and trample on free speech". The unsealed exhibits contain evidence underlying both parties' duelling motions for summary judgement, filed last month, in which they seek rulings in their favour to avert a trial. In one exhibit, Mr Murdoch emailed Fox News president Suzanne Scott on January 21, 2021, asking: "Is it 'unarguable that high profile Fox voices fed the story that the election was stolen and that January 6th [was] an important chance to have the result overturned'?

"Maybe Sean and Laura went too far. All very well for Sean to tell you he was in despair about Trump but what did he tell his viewers?"

Fox News host Sean Hannity (right) with Donald Trump.

Rupert Murdoch also suggested that a prime-time host like Laura Ingraham say "the election is over and Joe Biden won".

A sample ballot on a Dominion voting machine

'There'd be riots like never before'

In an earlier exchange with Ms Scott, Mr Murdoch wrote that it had been suggested to him that the network's prime-time hosts say something like "the election is over and Joe Biden won", according to Tuesday's filings.

Mr Murdoch told Ms Scott that some version of this would "go a long way to stop the Trump myth that the election [was] stolen".

According to Dominion's unsealed filings, Mr Murdoch emailed a friend, saying suggestions state legislators could change the election outcome — an idea then gaining traction on the right — "sound ridiculous. There'd be riots like never before".

"Stupid and damaging," Mr Murdoch continued, referring to a news conference by Mr Trump's then lawyer Rudy Giuliani.

"The only one encouraging Trump and misleading him. Both increasingly mad.

"The real danger is what he might do as president." 'Stop the media in its tracks'

These exhibits and other material included in Dominion's summary judgement motion are part of the voting machine company's effort to prove the network either knew the statements it aired were false or recklessly disregarded their accuracy. That is the standard of "actual malice", which public figures must prove to prevail in a defamation case.

Fox has said Dominion's "extreme" interpretation of defamation law would "stop the media in its tracks" and chill freedom of the press.

Fox's exhibits include more context of testimony and messages that it says Dominion "cherry-picked" and "misrepresented" in its summary judgement filing.

For example, Fox cites additional testimony by Fox Corp co-chairman and CEO Lachlan Murdoch, who said under oath he was "concerned" but "not overly concerned" by declining ratings after the election.

Dominion has alleged Fox continued to push the stolen election narrative because it was losing viewers to right-wing outlets that embraced it.

In another exhibit, Fox News host Hannity — quoted by Dominion as saying he "did not believe" Mr Trump's lawyer Sidney Powell's claims "for one second" during a deposition — went on to say that during the interview he was giving her time to produce evidence but stopped having her appear on-air after she failed to deliver.

A Dominion spokesperson said in a statement that the "emails, texts, and deposition testimony speak for themselves".

"We welcome all scrutiny of our evidence because it all leads to the same place — Fox knowingly spread lies causing enormous damage to an American company."

The trial, set to begin on April 17, is slated to last five weeks. Reuters Posted 8 Mar 2023

Fox News And The Big Lie P2

Trump Returns To Campaign US Presidency Campaign Trail Amid Stolen Election Lawsuits - Four Corners

-

MURDOCH AND ME

Rupert Murdoch may be the world’s most powerful private citizen. After running Murdoch’s Sunday Times of London for 11 years, a noted journalist reveals the triumphs and terrors of working for a 20th-century Sun King.When you work for Rupert Murdoch you do not work for a company chairman or chief executive: you work for a Sun King. You are not a director or a manager or an editor: you are a courtier at the court of the Sun King—rewarded with money and status by a grateful king as long as you serve his purpose, dismissed outright or demoted to a remote corner of the empire when you have ceased to please him or outlived your usefulness.All life revolves around the Sun King; all authority comes from him. He is the only one to whom allegiance must be owed, and he expects his word to be final. There are no other references but him. He is the only benchmark, and anybody of importance reports directly to him. Normal management structures—all the traditional lines of authority, communication, and decision-making in the modern business corporation—do not matter. The Sun King is all that matters.BY ANDREW NEIL

Other courtiers who believe they are your boss may try to tell you what to do, but unless they have the ear of the Sun King on the particular matter at issue, you can safely ignore them if you wish. All courtiers are created equal because all have access to the king, though from time to time some are more equal than others. Even Sun Kings have a flavor of the month—though those who enjoy that privileged post at the Murdoch court must remember that a month is not a very long time.

The Sun King is everywhere, even when he is nowhere. He rules over great distances through authority, loyalty, example, and fear. He can be benign or ruthless, depending on his mood or the requirements of his empire. You never know which: the element of surprise is part of the means by which he makes his presence felt in every corner of his domain. He may intervene in matters great or small; you never know when or where, which is what keeps you on your toes and the king constantly on your mind. “I wonder how the king is today?” is the first question that springs to a good courtier’s mind when he wakes up every morning.

The knack of second-guessing the Sun King is essential for the successful courtier; anticipation of his attitudes is the court’s biggest industry. It is fatal ever to make the mistake of taking him for granted.

All Sun Kings have a weakness for courtiers who are fawning or obsequious. But the wisest—among whom we must number Rupert Murdoch—know they also need courtiers with brains, originality, and a free spirit, especially in the creative media business. But independence has its limits: Sun Kings are also control freaks—and they are used to getting their way.

No matter how senior or talented or independent-minded, courtiers must always remember two things vital to survival: they must never dare to outshine the Sun King; and they must always show regular obeisance to him to prove beyond a doubt that, no matter how powerful or important they are, they know who is boss.

My problem was that I was not very good at either of these courtly virtues. I was too inclined to become a public personality in my own right; and I am not by nature deferential—to call anybody “boss” sticks in my throat. Looking back, it is remarkable I survived so long at the court of King Rupert and enjoyed it so much—a decade-long roller-coaster ride with the man who runs the world’s greatest media empire.

By 1983, Rupert Murdoch was looking for a new editor for the most prestigious of his properties, The Sunday Times. The then editor, Frank Giles, had been promoted from within in 1981, when Murdoch had moved Harry Evans from The Sunday Times to reinvigorate its daily counterpart, The Times. But Murdoch had always regarded Giles as a stopgap. Now he was impatient to efface the liberal, left bent of The Sunday Times and re-create the paper in his own, conservative image.

When Rupert summoned me to his office to offer me the job, I knew what was on the agenda—my old friend Alastair Burnet, with whom I’d worked at The Economist in the 70s, had tipped me off. I had been recommended to Rupert by mutual friends he trusted, and he saw in me an ideological soul mate. Also, since I had worked in America for three years as a reporter for The Economist, Rupert thought I could bring some American-style energy and drive to transforming The Sunday Times.

Despite his blunt, even brutal reputation, Rupert can sometimes take a long time to get to the point; this was one of these times. We talked about politics, satellite TV, Fleet Street—even the weather might have merited a mention. Eventually he turned to me and asked, “What do you think about being editor of The Sunday Times?”

Even though I knew the question was coming, I was still taken aback. I rambled on about not really having considered the possibility, the size of the challenge, and other banalities.

“I want you to take the paper in the direction we talked about,” he interrupted, as if this were only the latest in a number of talks we’d had about my becoming editor. “It must be strongly for democracy and the market economy. . . . There’s a lot of deadwood at The Sunday Times” he continued. “It’ll be a tough job to get rid of it. But I’ll be behind you.”

He was as good as his word. The biggest plus about having Rupert Murdoch as your proprietor is that he has no great social aspirations in Britain. He does not seek the approval of the Establishment, nor is he interested in their baubles, having turned down a knighthood and a peerage. This is a huge advantage for a newspaper editor out to make waves: when various parts of the Establishment objected to our coverage of the Thatcher government or the royal family or whatever powerful interest we had most recently upset, they often tried to work through Rupert to put pressure on me. He invariably resisted their blandishments.

I grew to learn that you could count on Rupert in a tight spot, even when he did not agree with what you had done. Our exposé of a bank account in which Margaret Thatcher’s son, Mark, deposited proceeds from various business activities in Oman that some tried to claim his mother had helped him obtain brought down on us the wrath of Margaret, Rupert’s heroine, but Rupert never criticized me for running the story. The most he ever said was that maybe we had given it too much prominence (and, in retrospect, he was probably right). When a constitutional crisis flared round our story that the Queen thought Mrs. Thatcher was not showing enough compassion for the dispossessed in society, and there were calls for my head, Rupert was as solid as a rock. Even when he disagreed with my attack on the royal family for playing golf and going to nightclubs during the Gulf War, and supporters of the monarchy were baying for my blood, he never gave them any joy.

In private, he leaves you in no doubt that he would sweep the royal family away tomorrow if he had the chance: he regards them as the apex of a class system that has held Britain back and slighted him on numerous occasions.

He could also be robust with complaining advertisers. Mohamed Al Fayed, the owner of Harrods department store in London, called me one night in the mid-80s to complain about a story we had run criticizing the way he was renovating the house in Paris once occupied by the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. I offered him space to put forth his point of view. He demanded a retraction and an apology. I refused. He threatened to withdraw all Harrods advertising from Times Newspapers.

“You can’t do that,” I said.

“Why not?” he asked. “It’s my advertising.”

“Because as of this moment,” I replied, “you are banned from advertising in The Sunday Times.”

He hung up, somewhat mystified. A little later the phone rang again. It was John King, the chairman of British Airways. He sought to intercede on Mohamed’s behalf. “Look, John,” I said firmly, “I’ve just banned Britain’s big-gest department store; I’m happy to ban Britain’s biggest airline too.” I was clearly in a bad mood.

“I think I’ll just stay out of this,” said John.

“Good idea,” I replied.

A half-hour later the phone rang again. It was Rupert, calling from New York. This, I thought, could be a tough one.

“I hear you’ve just banned our biggest advertiser,” he said.

“Yes,” I replied, explaining the circumstances.

“How much do Harrods spend with us?” he inquired.

“About £3 million,” I said nervously. There was silence at the other end of the line. I contemplated whether it would be better to back down or resign and become an unlikely hero of the liberal left.

“F— him if he thinks we can be bought for £3 million,” he said, and hung up.

Years later I visited the Windsor house in Paris. It seemed to me Mohamed had done a magnificent job of restoring the house, which was almost exactly as the Windsors had left it. But I did not regret my stance: once one advertiser knows you are a soft touch, they all do, and editing a paper free of commercial pressure becomes an impossibility. Anyway, once the ban was lifted, Harrods came back to The Sunday Times when it discovered no other paper could rival the impact of its advertising clout.

My relations with Rupert remained cordial for a lot longer than they might have partly because he was not living in London. It was tough enough for him to keep tabs on everything when he was based in New York running his new American media interests, including the New York Post and New York magazine (since sold), starting around 1976, but at least New York is on the same information network as London. When in the late 80s he moved to Los Angeles to supervise more closely his movie studio, Twentieth Century Fox, he found himself on another planet as far as

the news agenda is concerned. When he called from L.A. one day, I remember saying enthusiastically, “We’ve a great story for Sunday.”

“Great story?” he repeated. “They wouldn’t recognize one in L.A. if it came round the corner and hit them.” For all the power and glamour of owning a major motion-picture studio, Twentieth Century Fox, and an American television network, Fox Broadcasting Company, he will never give newspapers up: they are his first and last love.

There is a common myth among those who think Rupert Murdoch has too much power and influence: that he controls every aspect of his newspapers on three continents, dictating an editorial before breakfast, writing headlines over lunch, and deciding which politician to discredit over dinner. He has been known to do all three. But he does not generally work like that: his control is far more subtle.

For a start he picks as his editors people like me, who are mostly on the same wavelength as he is: we started from a set of common assumptions about politics and society, even if we did not see eye to eye on every issue and have very different styles. Then he largely left me to get on with my work.

But you always have to take Rupert into account: he is too smart to ignore. The snobbery of his British enemies has led them to regard him as something of a colonial hick because of the racy, down-market image of his tabloids and his strong Australian accent. They have had to learn the hard way that he is one of the smartest men in business, with a restless, ruthless brain that is more than a match for any British competition in newspapers or broadcasting. His mind is always buzzing, always up on the issues, and always original, which means his editors have to be on their toes if they are to keep up with him.

When I took the job of Sunday Times editor I imagined a short honeymoon before I would feel his wrath. In fact, he left me alone for most of the decade, keeping a wary eye on my progress from a distance, intervening only when he felt strongly about something. He would more often than not call me as the paper was going to press on Saturday (though there were weeks, sometimes months, when I would not hear from him at all) to find out what was on the front page and to share political gossip, which is Rupert’s stock-in-trade—give him some good inside information and he will go away happy, even if you haven’t a very good paper to tell him about.

He never barked orders to change what I was planning for the front page; he was invariably complimentary about our story lineup and would usually finish his calls with his customary courtesy, by thanking me for all my hard work. He only once ever directly tried (and failed) to influence the paper’s editorial line, when, in the 1990 Tory leadership contest, I decided to back Michael Heseltine’s attempt to oust Margaret Thatcher. He kept to the letter of his promises to Parliament of editorial independence when he bought Times Newspapers, consisting of The Times and The Sunday Times, in 1981. (He had earlier acquired two British tabloids—The Sun and the News of the World—and, in 1987, acquired the since folded Today.)

Editorial freedom, however, has its limits: Even when I did not hear from him and I knew his attention was elsewhere, he was still uppermost in my mind. When we did talk he would always let me know what he liked and what he did not, where he stood on an issue of the time and what he thought of a politician in the news. Such is the force of his personality that you feel obliged to take such views carefully into account. And why not? He is, after all, the owner.

Rupert is a highly political animal: even meetings about some technical matter having to do with color printing or pagination would invariably begin with an exchange of views on the current political scene in America or Britain. Business and politics are his only two passions: art, music, hobbies, poetry, theater, fiction, even sports (sailing may be an exception) have no interest for him. He is fascinated by politics for its own sake—but also because politics affects the business environment in which he operates.

Rupert expects his papers to stand broadly for what he believes in: right-wing Republicanism from America mixed with undiluted Thatcherism from Britain and stirred with some anti—British Establishment sentiments, as befits his colonial heritage. The resulting mix is a radical-right dose of free-market economics, the social agenda of the Christian right, and hard-line conservative views on such subjects as drugs, abortion, law and order, and defense.

He is far more right-wing than is generally thought, but will curb his ideology for commercial reasons (thankfully, he realized that a Sunday Times which entirely reflected his far-right politics, especially on social issues, would lose readers). In the 1988 American presidential election his favorite for the Republican nomination was Pat Robertson, the right-wing religious fanatic who claims to speak in tongues and have direct access to God, takes credit for having persuaded the Lord to spare his headquarters from Hurricane Gloria, and believes in a Jewish money conspiracy. “You can say what you like,” Rupert said to me during the ’88 Republican primary campaign, “he’s right on all the issues.”

Since the demise of Reagan and Thatcher, Rupert has found nobody to replace them in his affections on either side of the Atlantic. He supported Robert Dole in the 1996 presidential campaign without enthusiasm because he loathes Bill Clinton, but Dole is far too moderate a conservative for his tastes. So was George Bush: in 1992, Rupert reportedly voted for Ross Perot. He detests John Major with a vehemence few outside Rupert’s own circle have appreciated. He regards him as a weak, indecisive man, not up to the job.

Where political principle and business expediency clash, you can be pretty sure expediency will win. Despite his longstanding hatred of socialism, he is flirting with supporting the Labour candidate, Tony Blair, because Blair is heavily favored to become Britain’s next prime minister. Rupert would have far less time for Blair if the Tory government were doing better.

In the 80s, Rupert insisted on the hardest of lines against the “evil empire” of the Soviet Union. Yet he has cozied up to China, another evil Communist empire, in the 90s. This has required a wrenching U-turn in his attitudes toward China since the mid-80s, when Thatcher was negotiating with Beijing over the future of Hong Kong. Rupert wanted his papers to take a tough line to stiffen her resolve against China. “She should hold out,” he told me one day, “make no concessions, and tell the Chinese that there’s a Trident submarine off their coast: if the Red Army moves into Hong Kong they should be left in no doubt that we’ll nuke Beijing . . . though I suppose we could fire a warning nuke into a desert first,” he added, after a moment’s thought. There is no mystery about why Rupert has changed his tune: he will always moderate his political fundamentalism if it suits his business strategy. He had no business interests in the Soviet Union in the 80s; he is selling satellite TV to the Chinese in the 90s.

Iagreed wholeheartedly only with the free-market part of Rupert’s policy agenda, though, like him, I was also something of a Cold War warrior—the combination was enough to keep him satisfied about our editorial line most of the time. I had little time for his social agenda, especially that part inspired by America’s Christian right, to which he became more devoted as the 1980s progressed. He never struck me as a religious man—for Rupert’s religion is an extension of politics—and I believe he liked the Christian right for political rather than religious reasons (i.e., it produces blue-collar votes for conservative candidates and their agenda).

But he is also under the influence of Anna, his strong-willed wife, who is a staunch Catholic. Their marriage has lasted for almost three decades without a hint of scandal, despite Rupert’s long globe-trotting absences. This is just as well: given the kind of tabloids Rupert owns, many people would love to take revenge by revealing his infidelities. But I have never even heard a rumor of any. Rupert is actually not that interested in women.

Rupert and Anna are a close and even loving couple when together: I’ve seen them hold hands in a taxi and as they walk down the street. They talk regularly on the phone during the frequent times when they are far apart. Anna is formidable in her own right, with strong conservative social views that bolster Rupert’s (if anything, they are more stern than his). Her Catholicism has grown stronger over the years and had its effect on Rupert’s social outlook. He does not take much notice of her views on the business (he has ignored her pleas to stop the topless pictures in his London tabloids), but he will defer to her on family matters. And if Rupert was to fall under the proverbial bus tomorrow, many believe Anna rather than the children would come to the fore to try to fill his shoes in the company; she is certainly tough enough, though nobody is sure if she is ambitious enough.

Under Anna’s influence Rupert took up a fundamentalist anti-abortion position. Late one night he told me he was considering becoming a Catholic. “Since we both come from the same Scottish Presbyterian stock, you can hardly expect me to be over the moon at that prospect,” I replied, surprised at my own bluntness. He never raised the subject again—although some of his closest associates think he may have secretly turned Catholic.

There were times when The Sunday Times reflected very little of what its owner thought, but it did so enough of the time for us not to fall out. I was able regularly to criticize Margaret Thatcher, even though he adored her. Criticizing Ronald Reagan was a more risky business: Reagan was Rupert’s first love.

I admired Reagan’s economic and foreign policies, too, so there was not much friction between us. But I felt it impossible to support the president’s Iran-contra shenanigans. Rupert suffered our attacks on his hero in sullen silence because he knew Reagan had screwed up. But he regarded Oliver North, Reagan’s wayward White House assistant, as a national hero: “He sold weapons to the Iranians, freed hostages, and used Middle East money to finance the contras,” he once said to me admiringly. “The man deserves the Congressional Medal of Honor.”

He did not expect to see his particular views immediately reflected in the next edition of The Sunday Times after one of our many talks, though he would not have objected if they had been. But he had a quiet, remorseless, sometimes threatening way of laying down the perimeters within which you were expected to operate. His editors have to become adept at reading Rupert Murdoch: stray too far too often from his general outlook and you will be looking for a new job. It can be strangely oppressive, even when you agree with him: the man is never far from your mind. Rupert dominates the lives of all his senior executives. One who parted company from him 15 years ago confessed to me that he had only recently stopped dreaming about him. He still pops up from time to time in mine.

His first love is tabloid journalism (witness his willingness to sustain open-ended losses at the New York Post because of the enjoyment the paper gives him); it is what gets his juices going, and he has a brilliant populist sense for it. The wall of his office at Twentieth Century Fox in Los Angeles is covered with front pages from The Sun and the News of the World; there is nothing from The Sunday Times or The Times. Despite his privileged upper-middle-class background, he sees himself as an anti-Establishment man of the people (whom he once wincingly described on BBC TV as the “common people”) and believes his tabloids speak for their concerns, even though he has never had any real contact with Britain’s “common people” and mingles largely with Establishment types. He has a less certain touch for broadsheets. It has taken him almost 15 years to make a circulation success of The Times—and then only by spending tens of millions on price-cutting, which means it is still accumulating substantial losses. Though it would grieve him to think so, he has become an old-fashioned Times proprietor of the type he used to sneer at, keeping the paper going at a loss for years because of the power and prestige it brings its owner.

We were always broadly in agreement about the general direction of The Sunday Times. Any pressure he did exert, however, was in a down-market direction: he complained often that there was too much politics in the paper, that it was too issue-driven, and that it needed more human-interest stories and personality pieces. Sometimes the best reaction was to nod in agreement, then do nothing, in the hope he would forget; it usually worked. A confidant once explained that Rupert sometimes counted on his best people not to do his bidding—it allowed him to make broad attacks, which he enjoys.

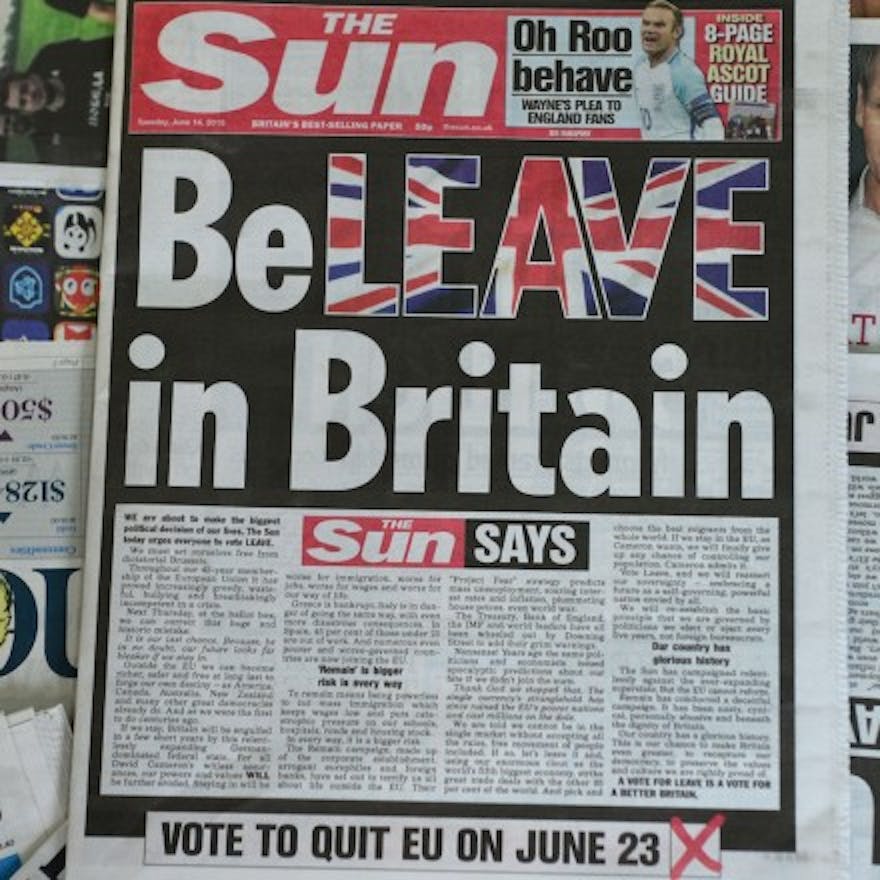

Rupert gives his broadsheet editors far more latitude than his tabloid ones. If you want to know what Rupert Murdoch really thinks, then read The Sun and the New York Post. His name is on the editorial page of the Post as “Chairman”; there are no names on the editorial page of The Sun, but his is written in invisible ink, since The Sun reflects what Rupert thinks on every major issue. He dislikes Europe, for example, which he associates with socialism, and rarely visits it even as a tourist. He despises the idea of a European Union—especially one that might interfere with his Pan-European business interests: hence The Sun’s strident anti-European line.

He is brutal with his tabloid editors, who live in fear of his calls. I only ever had a few harsh words with Rupert on the phone in 11 years; he nearly always treated me with respect, courtesy, and sometimes even kindness. Others were not so lucky.

Kelvin MacKenzie of The Sun endured almost daily “bollockings” from the man he always referred to as “the boss”—a steady stream of transatlantic vituperation and four-letter words was his regular diet for over 12 years, even though he ran a paper which netted his proprietor £70 to £90 million a year. “He treats the tabloid editors like dirt,” confirms John Dux, who was managing director in the early 90s at Wapping, Rupert’s high-tech non-union printing plant and Publishing center. “Kelvin used to go into great depressions after Rupert’s onslaughts. When you run the most successful tabloid in the world it is not nice being regularly told you’re a f— idiot by the owner.”

The abuse did not get better with time. A depressed Kelvin called me in February 1992. “I’ve just had the worst-ever four-letter tongue-lashing from Rupert,” he informed me. “I came very close to resigning last night. I’ve told Gus Fischer [Rupert’s top man in London in the early 90s] that I can’t take any more from that Australian bastard.

“Monty [David Montgomery, then editor of Today] has also been lambasted. In effect, Rupert said to him, ‘I don’t like your f— paper, and I don’t like you!’”

In the summer of 1993, Kelvin finally snapped: in the middle of a particularly bruising face-to-face encounter with Rupert in his office, Kelvin simply stood up, put on his coat, and walked out. His resignation followed within hours, by fax from home. He refused to take Rupert’s calls or answer his faxes. “I’ve gone too far this time,” Rupert confessed to Gus Fischer. “Will you intercede on my behalf?” It took Gus several days to talk Kelvin into returning, with Rupert even promising, “I’ll change.”

Rupert got his way and treated Kelvin with more respect after that. But things were never quite the same again: the whipping boy had finally stood up to the boss—and the boss was unsettled by it. Kelvin was soon moved from his beloved Sun to Sky Television, Murdoch’s multichannel direct-to-home satellite service, early in 1994. My belief is that Kelvin’s revolt in 1993 led directly to that unhappy and short-lived transfer, which, given the obvious fact that Kelvin and Sky’s boss, the cantankerous Sam Chisholm, were bound to fall out, could easily be construed as a disguised firing.

Kelvin was not the only one of Rupert’s editors to experience regular “bollockings.” Wendy Henry and Patsy Chapman used to live in fear and trembling of his calls when they were editors of the News of the World; they would call me almost every Saturday afternoon to ask if I knew where Rupert was, if he had called—and what kind of mood he was in. Patsy found it particularly tough to cope with Rupert’s telephone terrorism: she suffered a nervous collapse from the pressure and had to resign. Rupert made sure the company picked up the medical bills.

There was an element of the bully in this: Rupert ranted at Kelvin and others because he knew he could get away with it. I think Rupert sensed that I would be out the door before he finished his sentence if he talked to me in the same way; he never did. I always made it clear that if he was unhappy with my editorship I would not fight him to keep it. But I would not take being scolded like a schoolboy. Telephone terrorism is his weapon of choice to make sure his influence extends throughout his worldwide empire. He was often grumpy with me on the phone for no particular reason—and sometimes downright curmudgeonly, especially when the jet lag was bad. His global flying schedule added to his bad-tempered calls. He takes sleeping pills prescribed by a British doctor to help cope with the time-zone changes. Gus Fischer used to deliver a steady supply to him in America, but Rupert’s trusty personal assistant, Dot, was always worried that he would become too dependent on them. “I’ll take these,” Dot would say when Gus arrived, so she could ration their use. But if they helped him to sleep on planes they did not make him any more cordial when he hit the phone on arrival. These were the calls I came to dread, not because I feared their consequences but because they were unpleasant and pointless. It was never quite clear why he was in such a bad mood—whether I or Kelvin or some other editor was the cause of it or whether it was because he was dog-tired from his perpetual globe-trotting. There were simply times when he relished giving his underlings a bad time. You sensed the bleak atmosphere the moment you lifted the phone.

There was nothing you could say on such occasions to cheer him up or please him: he would quarrel with every remark you made, no matter how trivial, and nitpick the previous Sunday’s paper while praising the weakest stories of our rivals. He was determined to be miserable. If I had said, “Rupert, I’ve discovered a billion dollars in gold bars in the basement of our offices. I’m shipping them to you today,” he would have replied, “Why didn’t you find two billion?”

He punctuated such calls with long silences—traps inviting you to say something else with which he could disagree. You’d say something innocuous to keep the conversation going, like “Thatcher’s doing better these days,” and he’d snap back, “It won’t last.” Or I’d say, “The Sunday Telegraph was pretty weak,” and he’d reply, “They had better page-one stories than you.”

These calls were not designed to build morale; they left me angry and depressed. But over time I learned how to deal with them: when his “silent routine” began, I decided to say nothing. It worked. I remember one call when he seemed to have nothing to say—certainly nothing nice-and I just let the silence run. It became a test of wills, with the cost of a transatlantic call adding up as neither of us said anything. I could have gone and made a cup of tea. Just as I was about to crack, he finally said, “Are you still there?”

“Yes, Rupert,” I replied.

“Sorry, I have to go now,” he said. “Thanks for everything.” And off he went. I never got the silent treatment again.

There is a Jekyll-and-Hyde quality to Rupert: despite the bad-tempered calls, there were many times when he was courteous, even charming. Almost every time he called he began by asking if he was interrupting something important; of course, there is nothing more important to a courtier than a call from the Sun King. One Friday, when he was in London and I was behind with the editorial, I put a DO NOT DISTURB sign on my office door. I learned later that he had come across to see me, looked at the notice, and gone for a chat with the deputy editor, who advised him that the sign was not meant for him. “No,” said Rupert, “it means Andrew’s busy. I’ll leave him alone.”

Those times when he was in London (which became increasingly infrequent as his American interests expanded) had everybody on their toes. He would spend Saturdays going through budgets or administration with his managers, then wander across to my office as the first edition came off the presses. He would lay the paper on the lectern and noisily turn each page, stabbing his finger at various stories or circling them with his pen. He had the unerring knack of zooming in on the paper’s weaknesses— ones you had sensed as the paper was going to press but you hoped nobody else would notice. Rupert always did.

Sometimes he would leave you wondering if you had done anything right; it cast a cloud over your whole life. Other times, when he liked the paper, you felt you could walk on water, not just because the boss was happy but because Rupert’s newspaper judgment is unrivaled. It was part of his management style that he could leave you in a deep depression or on top of the world. I grew to resent that one man could have such an effect on me.

In the early years we had been quite close. During the mid-1980s I spent several Christmas Days in Aspen, Colorado, with the Murdoch family, who always made me feel welcome. Their Aspen house is a gargantuan alpine ski lodge with a swimming pool in the living room, but Christmas Day dinner was a delightful, low-key affair with only the immediate family present; I felt privileged to be there. The children—Elisabeth, Lachlan, and James—never behaved like spoiled rich kids and were always fun to be with. (Elisabeth, 28, and Lachlan, 25, are now executives in their father’s empire; James, 23, is trying his luck starting an independent rock recording label in New York.)

They are a happy family. Rupert enjoys spending time with his children when he can, though the phone never stops ringing to drag him away. Meal-times are informal and often the venue for spirited debate on politics and social matters. The family is not intimidated by him. Lachlan shares his father’s conservative views, James is more liberal, and Elisabeth is somewhere in between. Rupert has long regarded Lachlan as heir apparent, but Elisabeth has let it be known she wants to be in the running, too. Rupert, having dismissed the idea that his daughter could succeed him, now likes the rivalry between them. It was always a competitive household. When we played charades after dinner, the most obscure phrases—some in Latin!—were acted out. The same competitive instincts emerged on the ski slopes.

Both Rupert and I are enthusiastic if clumsy skiers. He had an obsession with finding the most difficult route down a slope. Once, he took a gang of his executives from Australia down a particularly challenging run; though most could barely ski, none said so for fear of losing face with the boss. I slipped away and took a fast, easy route to the bottom. When I looked up it was like the Battle of the Somme: bodies and skis everywhere, with Rupert at the bottom shouting at them all to get a move on.

On another occasion we took a Sno-Cat and went in search of powder off-trail on the back of Aspen Mountain; we spent most of the day on our backs or struggling to stay upright in the soft, champagne snow. I made it down one slope that had a small river at the bottom obscured by a recent snowfall. Rupert came hurtling after me. I waved frantically to warn him: “There’s a river here!” I yelled. “What?” he shouted, shooting past me, flying over the river, and landing flat on his face with a thump in the snow as he catapulted out of his bindings when the tips of his skis dug into the far bank. It was like a scene from a Tom and Jerry cartoon, and I collapsed in uncontrollable laughter. I then pulled myself together and rushed to dig him out before he suffocated.

For Rupert, everything in life is a competition. Gus Fischer told me of the time Rupert took him sailing round Sardinia on his huge new yacht. They had dropped anchor and taken the dinghy to a beach for a swim. Then it was time to return for dinner: Gus suggested they swim back to the boat. “It was a joke,” says Gus. “The boat was over a mile away on the horizon and the tide was coming in. But Rupert immediately replied, ‘Let’s do it,’ and started swimming out to sea. We made it, but there were times when I thought we were both going to drown.”

The boat was Rupert’s latest executive toy, but also the culmination of an Australian’s dream: sunshine and water. He had agonized over the huge expense of building it. “Maybe I should wait before buying,” he said to me. “It’s hard to justify the cost.”

“You work hard, Rupert,” I replied. “Why not enjoy the fruits of your success now?”

He thought for a moment. “You’re right,” he said. “Why should I wait till I’m too old to enjoy it?” His high-tech floating palace was built in Italy, providing long-term employment for an entire village. But by the time it was delivered I was no longer flavor of the month and never sailed on it.

Such examples of conspicuous consumption are rare for Rupert, who is his mother’s son in this regard. His Scottish Presbyterian background makes him reserved about spending too much on the baubles of billionaires. He has beautiful homes on three continents—including a stunning if somewhat soulless triplex overlooking Green Park in the St. James district of London and a 2,800-acre sheep farm in Australia—but he actually lives quite modestly, eating simply and drinking moderately, even preferring taxis to limousines. For a Sun King, his immediate entourage is very small. There is no kitchen cabinet that follows him around the world; he travels alone, but then, he is a loner.

It took him ages to acquire his own executive jet. He finally decided it was time when we arrived by commercial jet in Aspen one morning in the late 80s only to find that Barry Diller, then boss of Twentieth Century Fox (a recent acquisition of Rupert’s) had already arrived in his own jet. I could see the dialogue bubbles coming out of Rupert’s head with the words “It’s time I had one of these.” Within weeks, he did.

Even when I worked closely with Rupert I knew it would not last: he does not allow himself to make lasting friendships. “Don’t fall in love with Rupert,” Bruce Matthews, one of Rupert’s top London executives, warned me in 1987, when Rupert and I were very close. “He turns against lovers and chops them off.” The only people who are really close to him are his wife, his children, Helen, his sister, and his mother. He has no real friends. He does not allow himself to become intimate with anybody else, for he never knows when he will have to turn on them—it is always more painful to sack your best friend, whereas courtiers are disposable. “He cannot afford friends,” says Gus Fischer. “He has built his empire by using people, then discarding them when they have passed their expiration dates. It is not the sort of management style which lends itself to lasting friendships.”

“The management style of News Corporation,” said Rupert’s Australian chairman, Richard Searby, at a company seminar in Aspen which I had helped organize in the late 1980s, “is one of extreme devolution punctuated by periods of episodic autocracy. Most company boards meet to take decisions. Ours meets to ratify yours.” (Rupert was in the audience.) Searby was one of Rupert’s longest-serving lieutenants (though that did not save him when Rupert decided it was time to sack him, which he did by fax despite an association which went back to their school days), and he knew Rupert’s style well.

For much of the time, you don’t hear from Rupert. Then, all of a sudden he descends like a thunderbolt to slash and burn all before him. “Calculated terror” is how one of his most senior associates has described Rupert’s management style—that and a simple but superb weekly financial-reporting system combined with an eerie grasp of numbers explain why he is able to keep tabs on almost all that is happening. It is a combination which provides the backdrop to his many telephone calls, and it has its advantages: quick, unbureaucratic decision-making (providing you can get his ear), a daring corporate ethos, and a continuous adrenaline flow that keeps everybody excited. But it also has its drawbacks: senior managers are easily demoralized and undermined by Rupert’s cavalier behavior, which encourages sometimes irrational and unpredictable decisions.

Nobody in the company other than Rupert knows the whole picture. He relishes keeping even his most senior executives in the dark: a divide-and-rule approach which leaves them all feeling vulnerable. I knew many senior executives who spent far more time trying to second-guess Rupert than running the company. Kelvin MacKenzie once said, only half in jest, that the only real decision senior newspaper executives in London ever made was to toss a coin to decide who was going to call Rupert in New York to find out what they should do. This makes for weak management—but then, Rupert is surrounded by weak managers. Those who behave otherwise do not last long.

It is not just managers that Rupert regards as second-class citizens. He has little time for shareholders or board directors. Shareholders are a potential threat to his control of the global company he has built from scratch. He recognizes their interests only with reluctance. His view is that News Corporation shareholders should have no interest in current earnings or dividends; they should leave it to him to build long-term capital values—and anybody who buys the company’s shares should realize this. His boards are full of pawns who will do his bidding; he rarely consults them and only nominally seeks their approval. Gus Fischer told me of the time Rupert called to say he had just spent $525 million for 64 percent of the Asian Star satellite system, the Asian equivalent of Sky. “Could you call a couple of the directors and tell them?” asked Rupert.

“He had not bothered to seek board approval,” says Gus Fischer, amazed to this day. The Murdoch-family holding in News Corporation is down to only 30 percent; he once told me he would be nervous if it fell below 40 percent. But he still runs it as his personal fiefdom.

Those who survive longest at the court of the Sun King are a group of unthreatening Australians who have been with him for years. They are totally loyal to their master, and he is comfortable and relaxed in their company, though they suffer the rough side of his tongue when he feels like it. This they take without complaint. They have no choice: most are unemployable elsewhere at anything like the salaries and status they enjoy with Rupert.

They are the consummate yes-men, their purpose to reinforce his judgment in decisions the Sun King has already made, to nudge him in directions he has already decided to go, and to present no challenge to him. It always amazed me to see how the company prospered with such people in key posts. But they are the timeservers, whose job is to keep the show on the road. They are periodically supplemented by more talented folk whom Rupert hires temporarily for specific jobs he needs done. They might not last long and Rupert invariably falls out with them at some stage, but they serve their purpose at the time. Their intermittent presence is easy to accommodate in the company because there is no hierarchical management structure at News Corporation. If there is a structure at all it is a circle of courtiers, with the Sun King sitting at the center.

Rupert’s restless energy makes him prone to micromanagement. When I once complained about the food in the canteen, he spent part of a week sorting it out himself. He calls distribution or sales managers himself for the latest circulation figures and other information so that when he calls his top men he will know more than they.

The flaw in all this is that Rupert is actually not a very good manager—he does not have the patience for it. He is at his best as a consummate deal-maker, maybe the most formidable in the world for spotting an asset with potential, then acquiring it with the most imaginative financing methods. It is the excitement of the deal that attracts him. It awakens the gambler in him. It suits his short attention span. It makes him one of the world’s greatest business predators. But these very qualities make him an erratic manager.

“In fact, Rupert is a lousy manager,” says Gus Fischer bluntly. “He terrorizes those under him when he makes one of his flying visits: it takes weeks to restore their morale. He provides no leadership to inspire. He wants to take all the decisions himself—so he won’t delegate power. He wouldn’t even agree who should report to me. He prefers the tension between executives which his episodic intervention creates.”

John Dux agrees: “Rupert is the world’s worst manager. During his visits he should have inspired and encouraged his lieutenants. Instead he left them miserable and demoralized with his autocratic style and raging temper. It used to take weeks to restore morale after he had gone.”

Imitating the Sun King is always a great temptation, even for minor courtiers; it was something too many of Rupert’s managers found impossible to resist. He was brutal with them, so they were brutal in turn with their under-became a regular Saturday-night event; they were fun, work was the only topic on the agenda, and everybody enjoyed them. But word reached me that Rupert regarded them as an unnecessary extravagance—and that “living it up on a Saturday night at his expense” was just another example of how semi-detached I was becoming. I resented this ignorant long-distance carping and grew furious with the disinformation and innuendo being supplied for Rupert’s receptive ear. I confronted him in his office on one of his London visits.

“I hear you’re not happy with me,” I said bluntly. “What’s the problem?”

“You don’t seem that involved with the paper,” he said, almost embarrassed. Rupert does not like confrontations unless he provokes them, which he rarely does.

“That’s rubbish,” I snapped back. “It’s poison being poured in your ear. I’m more involved in the paper than ever before. Yes, I’m doing other things [I had started broadcasting on LBC, the London talk-radio station], but they complement what I’m doing at the paper, which remains my first priority. I’m not married, haven’t got a family, I live to work. Anyway, you should judge me not by the input but by the output of the paper; everybody thinks the paper’s going gangbusters, our Gulf War coverage is great, and sales are soaring.” He was somewhat taken aback by this blast. But I was angry.

The meeting cleared the air. For a while I had the best of all possible worlds: a disengaged, even remote owner from whom I heard less and less. The early 90s were the years when I hardly had a boss. I exploited this unprecedented independence to the hilt—I knew it would not last forever. At some stage, Rupert would inevitably seek to cage, remove, or destroy this monster he had unleashed.

By the summer of 1990 I was able to write in a private note that I was “now out of the Rupert Murdoch/News Corporation loop.” Placing The Sunday Times at the center of so many controversies had given me a certain celebrity, not to say notoriety, and going to bat for the newspaper in countless television and radio broadcasts had made me a public figure in my own right. Rupert resented it.

At first I could not believe my public profile was a problem for him. How could the billionaire owner of the world’s most powerful media empire, a man fêted by presidents, prime ministers, and captains of industry wherever he went in the world, be envious of my minor fame in Britain? It sounded too ridiculous even to consider. But I learned that it was the major reason behind his growing disillusionment with me.

“Do not underestimate how much Rupert resents your becoming a public figure in your own right,” I was warned early in 1994 by one of his closest confidants. “He hates the fact that you are better known, more regularly recognized than he is in Britain. He resents the way people talk about ‘your’ Sunday Times. He hates it when you refer to ‘my’ paper. He thinks your social life is a whirlwind of glamorous women and expensive restaurants. He does not like being upstaged like that. There is room for only one superstar at News International.”

“He used to get very annoyed when you got more or better publicity than he,” confirmed Gus Fischer three years later. “He couldn’t stand it. ‘One day he’ll get too big for his boots,’ he used to fume.”

Rupert was in his shirtsleeves when I arrived at his London apartment in April 1994. He had flown in from New York and looked tired and drawn. But he was in a good mood, having just made a deal with a Bombay businessman, who passed me on the way out, to expand his satellite-TV interests in India. As the two of us dined at a large round table on asparagus and flounder, served by a butler, he was at his most charming. This is also when he is at his most dangerous.

We talked about the newspaper: I gave several examples of how well it was doing, both in sales and stories. He agreed: “You’ve done a great job with the paper,” he said. “It’s a great paper. If I have one criticism it’s your tendency not to take any prisoners in a controversy. But that’s O.K. That’s you.”

We moved on to politics, discussing the relative merits of those who sought to succeed John Major. It was only when we adjourned to the sofas at the other end of the long room to sip chamomile tea that the conversation turned to me.

“We’ve talked about the paper and politics,” he said hesitatingly. “Let’s talk about you.” He proceeded to tell me about how his Fox TV network had concluded a multimillion-dollar deal to secure the rights to broadcast National Football League games on Sundays. He then explained how CBS, the previous N.F.L. broadcaster, had followed the games with 60 Minutes, its popular and prestigious newsmagazine show. That helped give it a lock on the Sunday-night ratings; it then did a substantial amount of on-air promotion before this big audience to preview shows it had coming up during the week. It had been part of the strategy which had made CBS America’s No. 1 network in its heyday. Rupert wanted Fox to develop its own version of 60 Minutes to follow the Sunday football games and similarly build Fox’s ratings. This is where I came in.

“I think we’ll need an American host for the show,” he said, “if we need a host at all [on 60 Minutes the reporters share the presenting]. But I see you as the senior of four reporters; you do the big international stories, the interviews with people like Clinton, the major investigations. I see you as the Mike Wallace figure in the show.”

I was not totally enthused by the prospect of going from being editor of one of the world’s great newspapers to a reporter on America’s fourth-rated network.

“Do you want a new editor for The Sunday Times, Rupert?”

“No,” he said emphatically, his eyes looking away. “I just thought it might appeal to you. Take your time and think about it.” It was 10:30 P.M. and his jet lag was now taking its toll: I thought it best to leave without committing myself to anything. We parted with a friendly handshake.

Early the next morning I consulted a couple of friends whose advice I valued and who I knew could keep a secret.

“It’s a f— insult,” one said angrily. “You’re one of the most successful editors in the world and all he can offer you is a reporter’s job in America? Why should you walk the plank? If he wants you to go he’ll have to do a lot better than that.”